- Home

- Wally Lamb

I Know This Much Is True Page 11

I Know This Much Is True Read online

Page 11

Up on the stage, Bulgy Eyes points his thumb at the husher. “You see this guy here? From now on, him and me are going to be looking for troublemakers. And when we find ’em, we’re going to kick ’em out and not give ’em their money back. And call their fathers. Understand?”

“Good,” Ma whispers from behind her hand. “It serves them right.”

Now everyone’s real quiet. Just sitting there. The lights go off. The movie starts up. Bulgy Eyes and the husher walk up and down the aisles. All the bad kids are being good.

Thomas pulls on Ma’s sleeve again. He says he can’t help it—he’s thinking about Miss Higgins so much, he has the runs. He wants Ma to go to the bathroom with him, not me. “Can you stay here by yourself?” Ma asks me. I say yes, and Ma goes up the aisle with Thomas. I hold his pencil box.

Slide it open.

His pencil is rough and bumpy where he chewed it. His eraser’s all wet. If Ray does tape up Thomas’s hands, he should do it while it’s still summer vacation because how could Thomas do his work? He’d get in trouble with Miss Higgins right off the bat. I bend Thomas’s eraser way, way back. It goes flying. It was an accident. Cross my heart and hope to die.

We’re not supposed to say that: cross my heart and hope to die. The nun says it’s the exact same thing as swearing. I didn’t say it, though. I just thought it.

Ray swears when he gets mad at Ma. One time he yanked her arm and gave her a black-and-blue, mark and I got so mad, I drew a picture of him with big giant daggers in his head. Then I ripped it up. At first, Ray wasn’t going to let us come to the movies today because movies are nothing but a waste of money. Then he changed his mind. One time, a long long time ago, he came with us to the show—with Ma and me and Thomas. It was on Sunday afternoon. The night before, he and Ma had a big fight and Ray made Ma cry. Then, the next morning, he was nice. He went to Mass with us and we ate at a restaurant and then we came to the movies. We saw The Wizard of Oz. Thomas spoiled it, though. Him and his stupid crying. Thomas always wrecks things.

They come back from the bathroom. “Push over, push over,” Ma says. Now Thomas is sitting next to me. He has a box of Good & Plentys. It’s for both of us to share, Ma says, but Thomas gets to hold it because the last time we went to the show and I held the popcorn, I kept stuffing it in my mouth instead of eating it nice so that Thomas wouldn’t get as much. “Take two at a time,” Thomas tells me, holding out the Good & Plenty box. “That’s the rule.” I tell him okay, but I take more than two every single time. One time, I put two fingers down real deep and get five. Thomas doesn’t even realize it. You can always trick Thomas. It’s easy. He doesn’t even know his stupid eraser’s missing.

Here’s what Thomas was crying about that time we saw The Wizard of Oz: those flying monkeys. The ones who work for the Wicked Witch and swoop down and kidnap Dorothy. Thomas was crying so hard that I started crying, too. At first, I didn’t even think they were scary, but then I did. Ray took us out in the lobby and yelled at us and said we were wrecking our mother’s whole nice day. The candy counter lady kept looking at us. That crippled lady. Ray said if we didn’t stop acting like two little scaredy-girls, he was going to take us to a store and buy us dresses. “Suzie and Betty Pinkus, the little scaredy-girls,” he said. That was when we were little—first-graders. If I saw those flying monkeys now, I’d just laugh because they’d be so fake.

Last year at recess, the third-graders used to sing this song:

First grade, babies!

Second grade, dumb!

Third grade, angels!

Fourth grade, bums!

This year, we can sing it. Thomas and me. Because we’re big. By the way, my muscles are bigger than Thomas’s.

Now I have to go to the bathroom. “Well, why didn’t you go before when your brother went?” Ma leans past Thomas and whispers. Her mouth is so close to my ear, she gets spit in it. I tell her I didn’t have to go until just now. It’s okay, I say. I’m big. I can go by myself. So she lets me. Thomas holds my pencil box because I held his.

I begin walking up the long, long aisle. At first, I’m a little afraid, but then I’m not. Ping! It misses. They better watch out. I’m Mark McCain. My father’s The Rifleman.

I like being out here in the lobby all by myself. At the soda machine, a man is buying his little boy a grape soda. I stop to watch the cup drop down, the streams of soda and syrup. “Boy, I’m thirsty,” I say out loud. The boy looks at me, but the man doesn’t.

Downstairs, in the room outside the lavatory, they have ashtrays with sand in them. There’s cigarette butts poking out of the sand. I play with them a little—the cigarette butts are bulldozers. I make bulldozer sounds.

Guess who’s in the bathroom? The husher. He’s leaning against the wall, smoking a cigarette and blowing smoke rings. Cigarette smoke swirls around his head. His mouth is a smoke-ring factory.

“I could have worked at the First National this summer,” he says. I’m the only one in there, but he’s watching himself in the mirror. I can’t tell if he’s talking to me. If he can even see me. Maybe I’m invisible. “But then I didn’t because he said he might let me run the projector. Only he hasn’t. Not once.” He makes another smoke ring—a big fat one. A smoke doughnut. He sticks his tongue out and pokes it in the middle. Follows it as it floats away.

“Guess what my mother saw one time in the show?” I say. “A rat.” I didn’t plan on talking. It just came out.

“Big deal,” he says, still looking at himself smoking. “We see ’em all the time in here. They come up from the river.” He has big red pimples on his forehead. “What do you think I cleaned off the top of the candy counter this morning? Rat crap, that’s what. We set traps. You can hear ’em going off in the basement—right during the movie sometimes. Snap! The springs are set so tight, it breaks their frickin’ backs.” He chucks his cigarette in one of the toilets, and it makes a little sound like tsst.

“If you find an eraser on the floor later, it’s mine,” I say.

He looks right at me for the first time but doesn’t say anything. Then he leaves. I have this whole huge bathroom to myself.

The urinals have big white pills at the bottom that smell like Christmas trees when you pee on them. When you piss on them. I say it out loud: “Piss on this!” Saying it—hearing the bad word echo in this shiny bathroom—gives me a little shiver. My hand shakes, wobbling the pee coming out. Now my soul has a dirty mark.

The bathroom door bangs open. Oh, no. It’s Ralph Drinkwater and Lonnie Peck. I zip up quick. “Hey, kid?” Lonnie goes. “Want some money?”

I tell him no and he grabs my wrist. I can see the X’s that Bulgy Eyes made on his hand and my hand. “Come on. For real. Hold your hand out flat.”

I know it’s a trick—he’s probably going to spit on it—but I do it. Lonnie grabs me by the wrist and jerks my hand up—makes me slap myself in the face. “Why you hitting yourself, kid? Huh?” he laughs. He does it again. Again. “Why you hitting yourself?” It doesn’t really hurt that much. It stings a little. I try to yank my hand away, but Lonnie’s bigger than me. Way bigger. How’s a third-grader supposed to fight someone in fifth grade who stayed back about fifty times?

“Hey, watch this!” Ralph goes. He rushes down the line of urinals, flushing. Turns all the sinks on full blast. Behind the wall, the pipes rattle and shake. Lonnie lets me go and starts pulling paper towels out of the paper towel holder. “Welcome to the fun house!” he screams.

I run. Out the door, past the ashtrays, up the stairs, through the lobby. Bulgy Eyes is leaning against the candy counter. “No running!” he goes.

When I get back to my seat, Ma stands up and lets me in. I don’t say anything about Lonnie and Ralph. About the husher or those rats. I sit in my seat Indian-style so no rats will walk on my feet. My heart is beating so hard I can feel it, and my face feels hot where I was slapping myself.

“Like my earrings?” Thomas says.

He’s taken his protractor and my protractor out of

our pencil boxes and hung them on his ears. I yank mine back. “Ow!” he goes. He pokes me and I poke him back.

“Watch the movie!” Ma begs. “It’s funny!”

But it isn’t funny. It’s stupid. Francis the Talking Mule is marching in a parade. Big deal. “How come you were wearing earrings?” I whisper to Thomas. “Because you’re a stupid little girlie?”

He elbows me; I elbow him back. “That’s enough, now, Dominick,” Ma leans over and whispers. “You be nice to your brother.”

“Say it, don’t spray it,” I tell her, right out loud. “You’re getting spit in my ear.”

If Ray was here, he’d wallop me one.

After the show, we walk back to the five-and-ten. We’re early for the bus. Ma says we can walk around inside but not buy anything. If we have time and we’re good, she might buy us an ice cream soda.

We enter the store, walk past the nuts and candies behind the glass case. Past the books, the comic rack, the toys. The five-and-ten has creaky floors. And a ceiling fan that goes thwocka-thwocka-thwocka. And a gypsy in a glass case that gives you your fortune for a penny. It comes out on a little card. The gypsy’s fake, but the cat on her shoulder is real. A real, dead stuffed cat.

“See that fan up there?” I ask Thomas. “If a real tall guy came walking by, that fan would chop his head right off.”

“No it wouldn’t.”

“Yes it would.”

Ma is looking at some paintings: clowns, mountains, two horses running through a river. An orange paper sign—GIANT ART SALE—moves in the breeze the fan makes. “Boys, look at this one,” Ma says.

She holds up a holy picture—Jesus floating in the sky. The Father and the Holy Ghost are up at the top, looking down at him. At the bottom, shepherds and other guys are hugging each other and looking up.

“Watch!” Ma says. She taps her finger against Jesus’ chest. When she moves the painting, you can see Jesus’ heart on fire. When she moves it back, it’s gone. It’s like magic. We make her do it over and over.

“Should I buy one of these?” Ma says.

“Yes!” we say. “Buy one!”

“Maybe next payday,” she says. “Come on. I’ll get you two your ice cream sodas.” When we pass the ceiling fan, Thomas asks Ma if it could chop off a tall guy’s head, and she says, “Oh, Thomas, what a thing to say.”

Thomas can’t finish his ice cream soda because he starts thinking about Miss Higgins again, so I finish mine and his. “You know what I bet will happen?” Ma says. “I bet I’ll come back on Thursday and all those paintings will be sold already.”

When we get up to go, she says, “Well, gee whiskers, if someone had treated me to ice cream and a movie when I was a little girl, I would have said, ‘Thank you.’”

“Thank you!” we say, exactly together. Sometimes I know what Thomas is going to say even before he says it. Ma will go, “What do you want for a sandwich, Thomas?” and I’ll go to myself, baloney and cheese. And then he’ll say, “Baloney and cheese, please.” I wonder if the Drinkwater twins can do that, too. I bet they can’t. They’re stupid. Penny Ann must be, anyway, if she’s staying back.

On our way out to the bus stop, we stop at the paintings again. Ma picks up the Jesus painting and points to the label on the bottom of the frame. “Who can read this?” she asks.

“’He is . . . ,’ “ Thomas says, then stops, stuck.

“’He is risen,’ “ I say. “’We are saved.’ “

“That’s right, Dominick,” Ma says. “Very good. Do you think I should just splurge and buy this?”

She doesn’t ask Thomas. Just me. “Buy it,” I say, like I’m the boss.

Ma takes crumpled-up money out of her change purse. The cash register lady wraps the painting in brown paper and asks Thomas and me if we are good boys at home. We say yes, and she gives us each a peppermint. We go outside and wait for the bus.

Ma rests the painting on the side of the building while we wait. We look and look and look, but that stupid bus won’t come. Ma says if it doesn’t come soon, supper will be late and Ray will get mad. She hopes he won’t get mad about the painting.

Ray is not our real father. That’s why we call him Ray. We don’t know who our real father is. I don’t know if Ma knows. I think he is very, very, very tall. I think he could beat up Ray. Our new painting is tall, but I’m taller.

Thomas says, “Look, Dominick. Communion!” He opens his mouth to show me the peppermint stuck to his tongue, but it slides off and falls on the sidewalk. Ma says it’s too dirty to put back in his mouth. Thomas cries. The bus comes.

Oh, no! It’s the grouchy bus driver with his stupid missing thumb. “Move to the back!” he says. “Come on. We haven’t got all day! Move to the back!”

The bus is crowded. We have to go way, way back. Ma tells Thomas and me to sit together on one of the long bench seats and she sits across the aisle, facing us. She puts her new painting in front of her. It’s resting on her knees.

Then the scary man gets on the bus (the man I would see and dream about my whole life after). He comes down the aisle toward us. He has crazy hair and whiskers and a big lump on his forehead. He’s mumbling to himself. His coat’s dirty. He squeezes into a small space next to my mother.

I don’t like looking at this man—don’t want to look at him—but I can’t help it. Ma shakes her head at me, which means, “Don’t stare.” But the man keeps staring at Thomas and me. He says something naughty—something about seeing “goddamned double.” Then he laughs. I know this man has a very, very, very dirty soul. I can tell Thomas is going to cry. I’m not even looking at Thomas, but I can tell.

The bus starts to move. Now the man is staring at Ma. Leaning toward her. He starts sniffing her like he’s a dog. Ma leans away from him as best she can. Her hand is up against her lip. Her other hand is holding the painting. Thomas starts to cry.

Someone will help us, I tell myself. But none of the other people on the bus pay attention to the man. His hand moves out of his jacket pocket. Moves over to our new painting and then behind it where my mother’s legs are. Ma’s hand against her mouth is shaking. Her other hand holds the painting tight.

She says nothing—does nothing—and I’m scared and mad and my whole head is boiling hot. . . .

At the next stop, Ma jumps up, hurrying Thomas and me up the aisle, banging the edges of the painting against things as she leaves.

“Yes, thank you!” she says when the bus driver asks if everything’s all right. We hurry down the steep, skinny stairs. The doors slap shut behind us. The bus jerks forward.

Then it stops again. The doors open.

The scary man is on the sidewalk, too.

Is he going to hurt us? Is he trying to steal our new painting? We run. Thomas’s pencil box has slid open and everything’s falling out. “Don’t stop!” Ma screams. “Don’t look back!”

But I do look back, and every time I do, the scary man is further away. Finally he just stops on the sidewalk and shouts something at us—something I can hear but not understand.

By the time we get home, my feet burn from all our running. All three of us are crying. Ma runs through the house, locking all the doors and windows and pulling down the shades. Then she sits on one of the dining room chairs and cries with her whole body. She cries so hard that she shakes the table and rattles the dishes in the china closet. Thomas and I stop our own crying to stare.

“Don’t tell your father what happened, now,” she says later, after she can speak again. “If he says, ‘How was the movie?’ you just say, ‘Good.’ If he gets wind of what happened, he won’t let us go to the movies anymore. That man wasn’t really bad. He just didn’t know any better. He was just crazy.”

Upstairs in her and Ray’s bedroom, Ma kneels on the bed and tap-taps a nail in the wall. Hangs the new picture. She promises Thomas she’ll get him another pencil box to replace the other one. “A nice one,” she says. “A better one than those junky things they gave out at the show.”

I’m tired now. I feel like crying. Why should Thomas get a nice pencil box when I have a junky one with no eraser? I thought this was going to be a good day, but it isn’t. Today is my worst, worst day.

“Who knows what might have happened today,” Ma says, “if Jesus hadn’t been there to protect us from that crazy man?” She sighs, stepping back to admire the new painting. I look, too. Jesus looks back, his arms extended toward us. When I move my head back and forth, his flaming heart blinks on and off.

“Someday,” Ma says, “I’m going to have Father LaFlamme come over and bless this painting. Bless our whole family. Our entire house.”

That night at supper, Ray catches Thomas chewing on his sleeve.

“Okay! That’s it!” he says.

Ray stands up and draws his belt from his pants. Loops it. Snaps it against the table. I think about those rats at the show, running through the dark basement, tripping the traps. Snap! Ray’s belt goes. Snap!

“Come on, now, Ray,” Ma says.

He jabs his finger at her. “You can just keep out of it, Suzie Q!” he says. “If you didn’t namby-pamby him all the time, he wouldn’t be like this!” He throws the belt down. Goes down to the cellar. Comes back upstairs with a roll of tape. “Am-scray!” he says, turning to me.

Out in the backyard, I can hear Thomas crying and choking and trying to breathe the way that dog tried to breathe when Mr. Grymkowski was pulling his collar. “I’m sorry, Ray!” Thomas keeps moaning. “Don’t tape my hands up, please! I’m sorry! I forgot! I’m sorry.”

Mosquitoes are out. Two bats crisscross the streetlight. An airplane’s red lights blink on and off in the sky.

In The Wizard of Oz, the Wicked Witch melts and the spell is broken and those flying monkeys turn nice. They weren’t even monkeys; they were men.

Our real father could be anyone.

The Rifleman.

Or that nice bus driver who finds candy in our ears.

Or even this pilot up in the sky. I run around and around and around the backyard, waving and flapping my arms so he can find us—Thomas and Ma and me.

I Know This Much Is True

I Know This Much Is True She's Come Undone

She's Come Undone The Hour I First Believed

The Hour I First Believed I'll Take You There

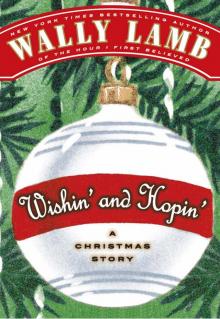

I'll Take You There Wishin' and Hopin'

Wishin' and Hopin'